Re: The Sphinxes Guarding the Lion Tomb Entrance at Amphipolis

Posted: Sat Mar 05, 2016 10:37 am

Zebedee, the last slide you show from the presentation is one used for comparison with the findings, not one from Kastas

All about Alexander the Great

https://pothos.org/forum/

Indeed. But they want a hoplite procession it seems.gepd wrote:Zebedee, the last slide you show from the presentation is one used for comparison with the findings, not one from Kastas

[32] G Now Alexander arrived at the district and found the rivers and the canals and the towns (?) arranged as described. From the land he saw a certain island out at sea and asked what it was called. The natives said: "Pharos, and Proteus dwelt there, where the memorial to Proteus is on a very high mountain, the one revered by us." Then they escorted him to what is now called the herōon and showed him the coffin. He sacrificed to the hero Proteus and, seeing that the memorial had fallen down from the ravages of time, he gave orders to have it set up at once and that the circumference of the city should be plotted.

They threw down grain and marked the line. But birds flew down and seizing all the grain flew away. And Alexander, disturbed at this, sent for soothsayers and related what had happened. They interpreted the events in this way: "This city which has been built will nourish the inhabited world and the men born in it will be everywhere. For the fowls of the air have flown all over the world."

Now they began to construct Alexandria from the plain of Mesos and the district took (?) its name from the fact that the building of the city began there. While they were occupied there, as happens, a serpent appeared and terrified the workmen who stopped working because of the arrival of the creature. This was reported to Alexander. He gave orders on the next day, whenever it came down, to capture it. So having received the order, when the creature appeared near what is now called the Stoa, they surrounded it and killed it. Alexander then ordered that the spot should be a sacred enclosure and he buried the serpent in it. He ordered that garlands should be hung there in memory of the Agathos Daimon whom they had seen.

Next he directed that the digging of the foundations should proceed only in one place, namely exactly where a great hill appeared which is called Copria. And when he had prepared the foundations of the greatest part of the city and planned it, he inscribed five letters Α, Β, Γ, Δ, Ε; Α for Alexander, Β for βασιλέυς {king}, Γ for γένος {son}, Δ for Δίος {of a god}, and Ε for the initial of the phrase beginning ἔκτισε {built the city}. Now many beasts of burden and mules were sacrificed. And when the herōon was consecrated, there came to the epistyle many troops of serpents and, creeping, they made their way into the four houses already built. And Alexander, present in person, consecrated the city and the herōon itself on the twenty-fifth of the month Tybi. So the door-keepers reverenced these serpents as Agathoi Daimones that had entered the homes. They do not shoot arrows at them, but even a pretence of shooting drives them away. And sacrifices were made to the hero as to the son of a serpent and the animals were festooned with garlands, and given a rest from their labours because they had worked hard and long for the founding of the city. And Alexander commanded that food be given to the guards of the buildings. They took the grain, ground it, and, keeping off wild creatures, (?) on the day quickly gave it to those dwelling in the buildings. So among the Alexandrians even till now this custom is preserved: on the twenty-fifth of Tybi the animals are festooned with garlands and sacrifices are made to the Agathoi Daimones by those who care for the buildings and gifts of domestic animals are made.

agesilaos wrote:

The Romance sheds light upon Andrew’s Alexander, it is not him but Proteus who is the ‘son of the serpent’ and the whole story is a Ptolemaic construct probably post 306 and Ptolemy’s assumption of the kingship it is attested in Eratosthenes ap Strabo. Once again the detail points to the third century and again rules out both Hephaistion and Olympias.

[32] G Now Alexander arrived at the district and found the rivers and the canals and the towns (?) arranged as described. From the land he saw a certain island out at sea and asked what it was called. The natives said: "Pharos, and Proteus dwelt there, where the memorial to Proteus is on a very high mountain, the one revered by us." Then they escorted him to what is now called the herōon and showed him the coffin. He sacrificed to the hero Proteus and, seeing that the memorial had fallen down from the ravages of time, he gave orders to have it set up at once and that the circumference of the city should be plotted.

They threw down grain and marked the line. But birds flew down and seizing all the grain flew away. And Alexander, disturbed at this, sent for soothsayers and related what had happened. They interpreted the events in this way: "This city which has been built will nourish the inhabited world and the men born in it will be everywhere. For the fowls of the air have flown all over the world."

Now they began to construct Alexandria from the plain of Mesos and the district took (?) its name from the fact that the building of the city began there. While they were occupied there, as happens, a serpent appeared and terrified the workmen who stopped working because of the arrival of the creature. This was reported to Alexander. He gave orders on the next day, whenever it came down, to capture it. So having received the order, when the creature appeared near what is now called the Stoa, they surrounded it and killed it. Alexander then ordered that the spot should be a sacred enclosure and he buried the serpent in it. He ordered that garlands should be hung there in memory of the Agathos Daimon whom they had seen.

Next he directed that the digging of the foundations should proceed only in one place, namely exactly where a great hill appeared which is called Copria. And when he had prepared the foundations of the greatest part of the city and planned it, he inscribed five letters Α, Β, Γ, Δ, Ε; Α for Alexander, Β for βασιλέυς {king}, Γ for γένος {son}, Δ for Δίος {of a god}, and Ε for the initial of the phrase beginning ἔκτισε {built the city}. Now many beasts of burden and mules were sacrificed. And when the herōon was consecrated, there came to the epistyle many troops of serpents and, creeping, they made their way into the four houses already built. And Alexander, present in person, consecrated the city and the herōon itself on the twenty-fifth of the month Tybi. So the door-keepers reverenced these serpents as Agathoi Daimones that had entered the homes. They do not shoot arrows at them, but even a pretence of shooting drives them away. And sacrifices were made to the hero as to the son of a serpent and the animals were festooned with garlands, and given a rest from their labours because they had worked hard and long for the founding of the city. And Alexander commanded that food be given to the guards of the buildings. They took the grain, ground it, and, keeping off wild creatures, (?) on the day quickly gave it to those dwelling in the buildings. So among the Alexandrians even till now this custom is preserved: on the twenty-fifth of Tybi the animals are festooned with garlands and sacrifices are made to the Agathoi Daimones by those who care for the buildings and gifts of domestic animals are made.

Gina Salapata, Hero Warriors from Corinth and Lakonia, Hesperia 66.2, 1997It seems likely, therefore, that the snake was considered in some Greek areas an

independent chthonic being and may have been worshiped. Despite its appearance

in very different religious contexts, the snake eventually assumed a primary association

as hero (or ancestor) signifier. It became the companion or attribute of a hero and

sometimes may also have represented the hero himself, as, for example, in the case of

Sosipolis. The precise reason behind this association, however, remains unclear to us. One

could argue that the snake, originally an underworld being, became associated with heroes

because heroes were persons who had died and who were closely attached to their real or

alleged graves, or, more likely, because this animal, so intimately connected with the earth

and tied to particular locations, better expressed the restricted locale and autochthonous

nature of most heroes, especially founders and eponymous heroes. It is also possible that

in the minds of the ancients the snake represented such figures of the remote past as the

Hesiodic Silver Generation, the hypochthonioi, who were honored after their death and,

by definition, resided under the earth. The hero, therefore, being buried and attached to a

specific location, would have kept company with the original subterraneous inhabitants,

who were anonymous and collectively embodied by the snake.

Another commonly argued explanation is that the snake was first the manifestation of

all chthonic spirits, including heroes; with the advance of anthropomorphic concepts it

was demoted, becoming the sacred animal of some chthonic gods and heroes and thus

their attribute. Its presence then would indicate that a scene takes place in the Underworld

or is to be connected with the chthonic powers.

There's no real problem regarding the dating of the shield. Agesilaos is essentially right. Greek/Macedonian cavalry did not use shields in Alexander's day (Not least because the 12foot 'xyston' lance really required two hands ). The large circular shield with spine is a Celtic type that can be firmly dated to the period 300-270 BC. They were likely introduced following the usage of so-called 'Tarantine' cavalry whose armament of missiles/javelins and shield was found to be effective. The larger Celtic spined type would have been encountered by Pyrrhus' troops in Italy c. 281-275, and may have been, and probably was, introduced to Greece by his cavalry. Alternately it could have been adopted following Celtic invasions of Greece around the same time, when the Celtic long infantry shield called by the Greeks 'thureos' was also adopted.If the dating of the shield is a problem, then let that be the problem...

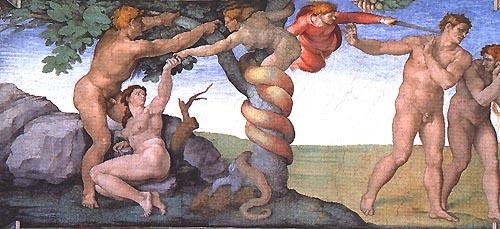

That is not a statement of my position. I have not said anything that might suggest that that is my position. My position on the serpent in a tree is that among the sensible candidates with other associations with the Amphipolis Tomb and consistent with the (now) established period of the tomb, it is Olympias who has the main association with serpents apart from Alexander himself (who is not a candidate and whose connection with serpents arose via Olympias). It is also my position that citing random ancient references and sculptures that have nothing in the way of a particular connection with the Amphipolis Tomb constitutes an anti-confirmation bias, for it is of course true that there are enormous numbers of other depictions and references to serpents in antiquity that have no connection with Olympias and no connection with the Amphipolis Tomb. And if we are being comprehensive, why constrain ourselves to antiquity even? Below is another famous serpent in a tree. It has at least as strong a connection with the Amphipolis Tomb as others that are being cited here, and the story it relates is ancientamyntoros wrote:I don't think people are merely questioning the origin of the relationship of Olympias with snakes. It's more your conviction that where there is a snake it must mean Olympias, as if there could be no other reason for the portrayal of a serpent. If you don't see this as an indication of confirmation bias you might want to make a more thorough examination of ancient Greek religious beliefs.

There is when the proposal is that what we're seeing is a spearpoint placed against the shieldXenophon wrote: There's no real problem regarding the dating of the shield.

A statue of Alexander the Great from Alexandria, where he was remembered as the Son of the Serpent.

Still, since Alexandria, the only place the ‘Aegis-bearing Alexanders’ are found they are irrelevant to Amphipolis, not least because they are probably copies of the cult statue which was not unveiled before Ptolemy moved his capital to Alexandria between 312 and 285, see Stewart ‘Faces of Power’ pp.246ff hereThe matter is not controversial. There is a whole class of these Alexander statuettes from Alexandria, including the one you might know from the British Museum (below). Obviously, this is yet another strong connection with Olympias since it potentially alludes to the story about Zeus-Ammon visiting her to father Alexander in the guise of one of her pet snakes.

Hi Xenophon, is there a reference for that? Not sure where to read about it. The only thing that commonly comes up is that Celtic shields were oval shaped, so is the circular type a Macedonian adjustment?Xenophon wrote:The large circular shield with spine is a Celtic type that can be firmly dated to the period 300-270 BC.